Baltimore’s CFG Bank has grown its own way, quadrupling in size in just a few years

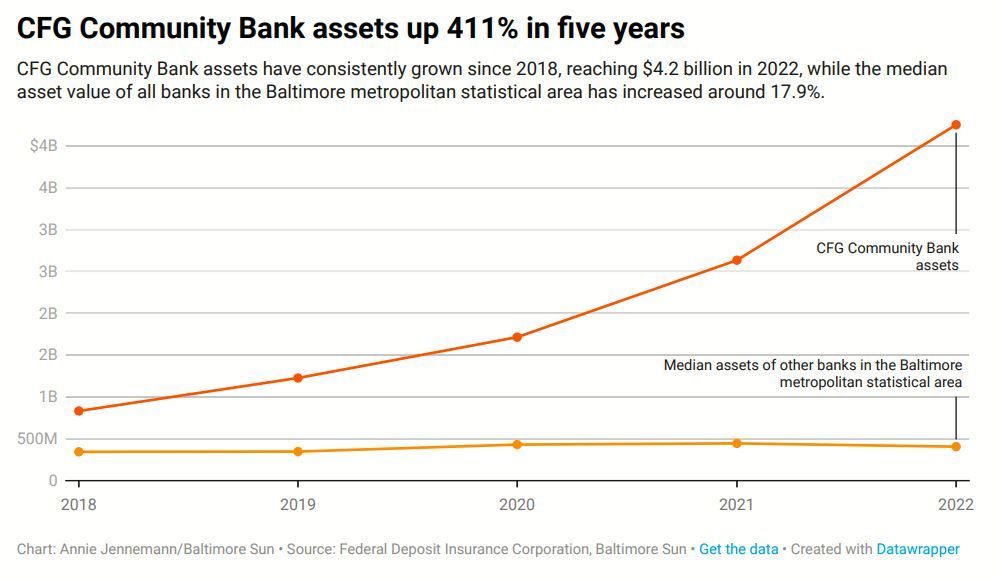

Just about every bank based in the Baltimore region is about the same size as it was five years ago, or a little bigger, save one — CFG Bank more than quadrupled its assets, deposits and profits since the end of 2018.

With about $4.25 billion in assets at the end of last year, CFG remains a small player nationally, but the Baltimore County bank has blossomed into the biggest bank headquartered in the metropolitan area and fourth biggest in Maryland, even as rising interest rates, depositor worries and bank failures roil the industry.

Recently, CFG has taken steps to boost its profile to match its growth. The bank bought the naming rights for the newly renovated CFG Bank Arena in downtown Baltimore and is moving its headquarters to the Baltimore Peninsula project in Port Covington.

The privately owned bank’s story started decades ago when Jack Dwyer, now 66, went to work for the health care lending subsidiary of a Maryland bank and quickly realized the opportunity in nursing homes: baby boomers needed places to live when they aged.

“You can build a nursing home every day … for the next like 35, 40 years, and you can never meet the demand that’s out there,” Dwyer thought at the time.

The federal government helps finance the acquisition, renovation and construction of nursing homes, but Dwyer said it can take a year to get the paperwork approved. He formed Capital Funding Group to become a bridge lender for the nursing home industry.

During the 2007-2008 financial crisis, his credit dried up, Dwyer said, and he never wanted to put himself in that position again. “‘I’m gonna buy a bank,’” Dwyer recalled thinking. “A few of my friends told me I was out of my mind. But I didn’t think so.”

In 2009, Dwyer’s company bought AmericasBank, a Baltimore County bank that had loaded up on home mortgages as the housing market collapsed. He changed the bank’s strategy, steadily growing lending to the nursing home industry.

Soon, he realized he was losing out on bigger deals. As a small bank, CFG couldn’t lend a billion dollars to a company trying to complete a merger. There are regulations about loan size and capitalization requirements. Instead, the bank was forced to syndicate such loans, which meant cobbling together the money for a loan from several other banks. Dwyer said most businesses would rather just go to a big bank that could loan the money outright.

So he came up with a way to lend like a big bank. Dwyer said CFG partnered with a New York-based institutional investor to raise billions of dollars for a fund controlled by another Capital Funding Group subsidiary. CFG declined to name that partner. The fund effectively gives CFG more leverage to make bigger loans, he said, allowing CFG to make more money from origination and management fees.

During the coronavirus pandemic, CFG would have been limited by the size of its deposits to making loans worth tens of millions of dollars, Dwyer said. Instead, the bank was able to finance a $660 million deal in 2021 for the acquisition of a group of nursing homes in Virginia. The bank declined to release more information about the deal, but its executives explained how such deals generally work.

When CFG originates a big loan, that loan is immediately securitized, meaning split into different tranches, organized by risk, and sold. The fund — which is not on the bank’s balance sheet — takes the “B-Piece,” the riskier tranche that is last to be repaid, while segments of the “A-Piece” go to investors. CFG holds onto 5% of the loan.

“No little banks do anything like that,” Dwyer said. “To our knowledge, we’re the only one really doing that.”

Dwyer said CFG’s fund helped it land bigger deals, while retaining the personal touch of a small bank. “

[Our clients] can pick up the phone and call me anytime they want. And they do,” Dwyer said. “That typically doesn’t happen at a big bank. Sometimes you struggle to even figure out who you can talk to.”

From 2018 to 2022, CFG’s assets grew from $832 million to $4.25 billion. Profits rose from $25 million to $114 million.

No bank in the Baltimore region comes close to matching that rate of growth, and CFG’s leadership team expects to keep growing

That growth comes as the banking industry is coming under increasing scrutiny. Three fast-growing banks elsewhere failed this year and interest rates continue to rise to their highest level in more than 15 years, squeezing bank margins.

The three failed banks were all relatively large — each had more than $100 billion in assets — but Michael Faulkender, a professor and former U.S. Treasury official, said this latest banking crisis could affect institutions of all sizes.

Faulkender, the dean’s professor of finance at the University of Maryland’s Robert H. Smith School of Business, said there is a balancing act at the core of nearly every lender. Any bank can tip into trouble if it has too many long-term assets and short-term depositors pull out their money, he said.

Silicon Valley Bank, for example, failed in March because it purchased a large amount of U.S. Treasury bonds during the pandemic, when interest rates were at historic lows, Faulkender said. As interest rates rose, these long-term securities lost value, he said, spooking depositors who withdrew their money. In other words, there was a bank run.

“That liquidity transformation issue is the fundamental challenge in banking,” Faulkender said. “Anybody could be caught in that dilemma if you are doing any kind of low-interest lending funded out of deposits.”

But unlike Silicon Valley Bank, CFG Bank has not loaded up on low-interest, long-term securities and its portfolio is relatively diversified, said Mary Ann Scully, a former banker and dean of Loyola University Maryland’s business school. Scully founded Howard Bank in 2004, steadily growing the bank until its sale to First National Bank of Pennsylvania in 2021.

Scully said she knows the team running CFG Bank and reviewed some of its public filings.

“I really admire what they’ve done in the last few years,” said Scully, whose Howard Bank in 2017 acquired the first Maryland bank — 1st Mariner — to buy naming rights for what was then known as the Baltimore Arena.

According to CEO Bill Wiedel, CFG’s loan portfolio is about 40% in health care and 20% in apartments, with the remainder being traditional banking services. CFG is one of the few Maryland banks working with the cannabis industry; the drug remains illegal federally. It is a growing segment, Wiedel said, but is less than 5% of its loan portfolio.

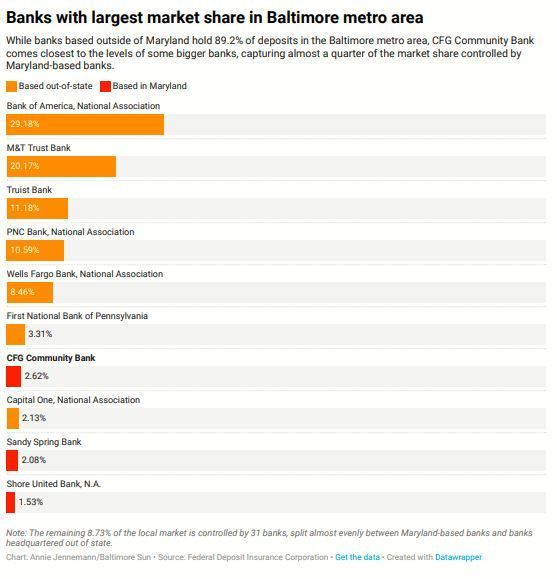

Despite its growth, CFG is a relatively small fish in Baltimore banking. Like most metro areas, the region is dominated by national firms, including Bank of America, M&T Bank, Truist Bank, PNC Bank and Wells Fargo. In 2022, those five banks collectively had more than 350 branches and held nearly 80% of all the deposits in the Baltimore metro area,

according to federal regulators.

CFG, meanwhile, held 2.6% of the region’s deposits, making it the metro area’s seventh-biggest bank by market share, but the largest one based locally. Unlike those bigger banks, CFG has resisted expanding its physical footprint, with just two branches and a cashless office in Annapolis. That’s fewer than almost every bank headquartered in Maryland.

“We actually look at that, in a weird way, as a benefit. And that’s what enables us to pay 5% on our money market rate, quite frankly. Because we don’t have the expense of a huge branch network,” Wiedel said. “With all the electronic banking that’s out there now, branches just aren’t as valuable as they used to be.”

That’s not a normal bank strategy, said Bert Ely, a banking consultant based in Alexandria, Virginia. “It’s an atypical banking strategy for a bank its size, which is not bad, it’s just not typical,” Ely said. “Every bank has risks. This bank has a somewhat atypical risk profile by virtue of how it’s operating.”

Most banks expand through mergers and opening more branches, Ely said, and it’s rare for a multibillion dollar bank of CFG’s size to be privately owned. Still, after reviewing its financial reports, Ely called it a “good, solid bank.”

CFG Bank plans to add a branch at its new headquarters at Baltimore Peninsula, a 235-acre development in South Baltimore. CFG will move 250 workers there from an office in the Bare Hills area just north of the Baltimore County line.

The bank also planted a flag downtown with the new name on the arena, negotiated in a private deal with the company that manages the facility.

Colin Tarbert, CEO of the Baltimore Development Corp., called these decisions a “great signal from the private sector that Baltimore has a bright future.”

“I don’t think a company like CFG Bank, which is clearly growing, would move to Baltimore City if they didn’t think the city was also on a great track,” Tarbert said.

As for the future, Dwyer said his bank is raising three additional funds to lend more aggressively in senior living, apartment buildings and cannabis. “This is going to be the opportunity of a lifetime,” Dwyer said. “Most banks are on the sidelines.”

Read article from source, The Baltimore Sun

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!